Ocean Watch posted May 1, 2020

A sculptured slipper lobster, Oahu. © Susan Scott

While snorkeling last week on the North Shore, I found something I’ve never seen drifting in the ocean before: a sculptured slipper lobster. The sculptured is one of five slipper lobster species found in Hawaii waters.

The scientific name of this lobster is, oddly, Parribacus antarcticus. Why a naturalist in 1793 named this tropical-only species after Antarctica remains a mystery to me. In my search for an answer, though, I got a clue. Aristotle (385 BC–323 BC) named a slipper lobster arctus.

Hawaiians called all slipper lobsters ula-papapa, meaning flat lobster.

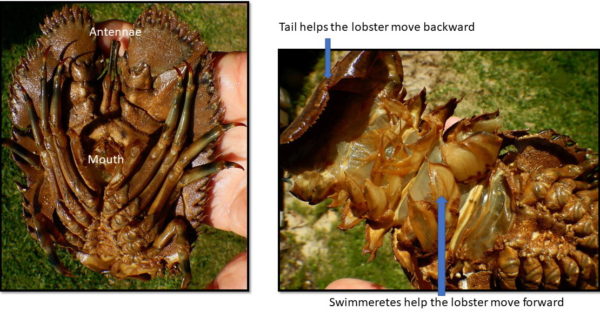

Unlike North American lobsters, slipper lobsters don’t have pincers, nor do they have the long antennae, (the “spines”) of spiny lobsters.

A baby slipper lobster, species unknown, I found on Lanikai Beach in 2011.

All lobsters have two pairs of antennae, but in slipper lobsters one pair of antennae evolved into thin, flat paddles useful for digging up prey. Because of these shovel-like tools, the creatures are also known as shovel-nosed lobsters or, my favorite, mitten lobsters.

During the day, slipper lobsters hide in cracks and holes in the reef at depths from 2-to-60 feet. At night, the creatures venture out to hunt on four pairs of sharp-tipped legs.

Three pairs of jawlike appendages crush and shred the snails and bivalves that the lobster finds during its forays, passing the food into the mouth below.

Flattened projections toward the rear of the lobster, called swimmerets, help the lobster move forward. To go backwards, the animal uses its flat wide tail.

To see a live, walking sculptured slipper lobster, check out this short video: https://youtu.be/A4-4sXb21JM

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4-4sXb21JM[/embedyt]

The sculptured slipper lobster I found is Hawaii’s most common slipper species. Most are smaller than the maximum growth of 7 inches, making the species too small to be commercially valuable. Individuals, however, fish for them.

Once in the 1990s, an acquaintance ordered a sculptured slipper lobster for me as a pupu in a pricey French restaurant. I felt terrible eating such a tiny, and relatively rare, animal. It was my last.

Two other Hawaii slipper species, the ridgeback and scaly, grow to 16-20 inches long, and are fished for food, but with legal restrictions.

My sculptured slipper lobster was adrift because it was either dead, or it had molted its shell to grow bigger. I’m not sure which. The slit across its back looked like the opening that molting lobsters back out of, and the inside was empty of guts. Even so, the shell was hefty and firm, far from the fragile spiny lobster molts I’ve found in the past.

It doesn’t matter whether the little lobster died a natural death or lives on in a bigger body. In either case, its shell was a gift.