Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

December 1, 2014

Why don’t giant clams growing deep inside living coral heads get squished by growing coral?

My friend asked me that in Palau as we snorkeled over brilliantly colored clams sunbathing in all their glory from their coral head homes.

A giant clam lives on its coral home in Palau.

A giant clam lives on its coral home in Palau.

©2014 Susan Scott

Good question. I did not know.

Then last week Mary sent me a link to a marine aquarist magazine article that explained how giant clams bore. It was a well-written piece, with references, but I wondered: Why do people who keep home aquariums want to know about giant clams?

Giant clams, I learned, are suitable for the home aquarium trade because despite their family name, some of the eight giant clam species are small. Six of the little ones, as gorgeous as their colossal cousins, are sold as saltwater pets. Besides enjoying the clams’ unique colors and patterns (no two clams are alike), aquarists like giant clams because they’re hardy, grow fast and need little care.

This is good because people also like to eat giant clams of all sizes, and as a result, they’re scarce or absent in most unprotected areas of the tropical Indian and Pacific oceans. Today most species are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature red list of threatened species.

But there’s hope. Because the clams do well in tanks, aquaculture farmers grow giant clams throughout the Pacific. Some of the young clams go to the aquarium industry, but the clams grown in state-sponsored farms get transplanted in their native habitat.

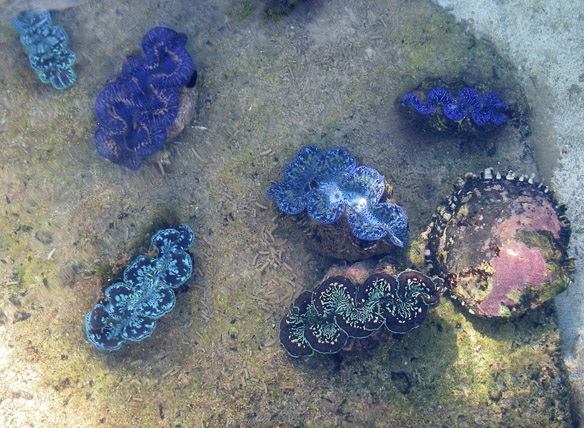

Giant clams being farmed in Aitutaki, Cook Islands.

Giant clams being farmed in Aitutaki, Cook Islands.

Courtesy Scott R. Davis

Tank-grown clams never bore into coral heads after release, but remain free-standing. If born on the reef, however, baby clams often dig in. After drifting in currents for about 10 days, a larval clam drops hinge-side down onto a coral head, anchoring itself with threads protruding from a hole where the clam’s two shells meet.

Also protruding from the hole is a flap of tissue that excretes a weak acid, killing the coral bodies beneath it and weakening the limestone below. (Only the top layer of a coral head is alive. The bulk below consists of the living coral’s long-dead ancestors.) Meanwhile, topside, the clam’s lovely “lips” release a chemical that keeps budding coral polys at bay.

The exposed lips also contain algae that feed the clam and iridescent color cells that act as sunscreen to protect the clam’s soft parts from burning. The resulting color combinations make giant clams of all sizes look like brilliant smiles lighting up the face of the reef.

Thanks, Mary, for the question and link. The expression “happy as a clam” finally makes sense.