July 5, 2023

With the ambitious goal of seeing kōlea chicks, 19 Hawaii Audubon Society members, including Dr. Wally Johnson, and I spent the last week of June traveling the tundra near Nome, Alaska, a famous gold rush town of about 3,700. I call our goal ambitious because I’d been to the area in 2018 with plover expert, Wally Johnson, and learned how hard it is to find a plover nest with eggs, let alone one with chicks still in it. Like chickens, as soon as newly hatched chicks are dry, they leave the nest to forage for food.

With that in mind, we called our trip “Kōlea Quest” and prepared ourselves. Even if we didn’t see chicks, we would appreciate seeing where it happens and enjoy Nome’s spectacular plants, animals, rivers, and mountains. (For more story and photos, see Kolea Count News/Nome)

Nome roads are mostly unpaved. Kapiolani Community College student, Emma Ho, declared our mission in dust. ©Susan Scott

We 21 plover lovers (including our outstanding Nome guide, Carol Gales) traveled in the three vehicles above. The vegetation below the road is typical terrain in the vast miles of tundra. ©Susan Scott

A view from Council Road. The other side of the road is the Bering Sea. Nome is located on Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, accessible only by air, boat, or dog sled. Nome is the end of the famous Iditarod dog sled race. ©Susan Scott

The first order of “Kōlea Quest” was for Wally and his long-time Anchorage-based research assistants, Paul and Nancy Brusseau, to look for the Pacific Golden Plovers they studied in the past. Males usually build their soft lichen nests in the same area year after year, and some may reuse the same nest from the previous summer.

Although kōlea have learned to live with us humans in the main Hawaiian Islands, they are not people-friendly in their Arctic nesting grounds where predators abound. Observers have to spot a kōlea either flying or foraging, and then follow it with binoculars to its well-camouflaged nest.

Craig Thomas with Paul and Nancy Brusseau, our team spotters, keep track of a kōlea they saw flying. ©Susan Scott

While one person watches where the parent settled, another person walks toward it, guided by radio communication from the person who has eyes on the bird.

Paul carefully approaching the area where the bird landed. ©Susan Scott

Once a walker approaches a nest, the kōlea parent flies off and behaves as if its wing is broken, a ploy to lure a predator away from the eggs. This leaves the human walker with the tricky job of finding the nearly invisible nest, but not stepping on it.

Even when standing next to the nest, I couldn’t see it. A member of the team pointed it out for me. ©Susan Scott

This is the typical “broken wing” posture of a male trying to lure us away from the nest. ©Susan Scott

When a nest is discovered, however, workers can’t flag it because the parent may not return to an altered neighborhood. To relocate a nest, researchers create their own tundra cairns, count paces, and triangulate with background scenery.

While the nest finders worked, the rest of us explored the three roads leading out of Nome. The tundra delivered. We marveled over wildflowers, lichens, and tiny plants that hide the birds so well.

Wildflowers bloom here and there throughout the tundra. ©Susan Scott

The shallow puddles that lie between grassy tufts harbor mosquitoes and other insects that nourish birds and their chicks. ©Susan Scott

Back at the hotel, the research team had good news: They had found an accessible plover nest containing four eggs. Several days later, the shells contained tiny holes and cracks. The nest team could hear the chicks’ peeping, but the eggs had not yet hatched.

Cracks in the eggs were barely visible but we could hear the chicks peeping. ©Susan Scott

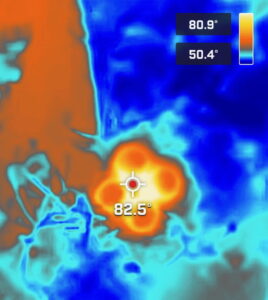

Paul’s infrared photo of the eggs measured their heat. Temperature color scale upper right. ©Paul Brusseau

Sadly, it was time to leave. The next morning, while the nest finders checked the eggs one last time, the rest of us checked our baggage in at the tiny airport. As we were discussing what to do with the two hours we had before going through the TSA line, one of the nest finders sent a text with no words, but just one joyful photo: four newly hatched kōlea chicks.

Chicks hatch one at a time in the order the female laid them. The last chick, top, is till wet. The pink knobs are the newborns’ folded legs. These parents have already picked up the eggshells, white and visible to predators, and dropped them far from the nest. ©Susan Scott

It was the most organized our group had been all week. In a flash, we were in the vehicles, at the site, and tiptoeing through the tussocks. At the nest, we quickly took our photos, and left those precious babies and parents in peace.

I know that during our exit, each of us was silently thanking the plovers, the search team that included Dr. Wally Johnson, our trip organizer, Dr. Wendy Kuntz of KCC, the Hawaii Audubon Society, and of course, the universe for giving us this once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Back at the airport, long-time Audubon board member, Pat Moriyasu, summed up the trip perfectly.

“In Nome,” she said, “we struck gold.”