Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

August 13, 2012

When snorkeling, I carry my much-loved underwater camera around my neck on a long lanyard that allows me to shoot close-ups without taking it off.

Photo by Susan Scott

Photo by Susan Scott

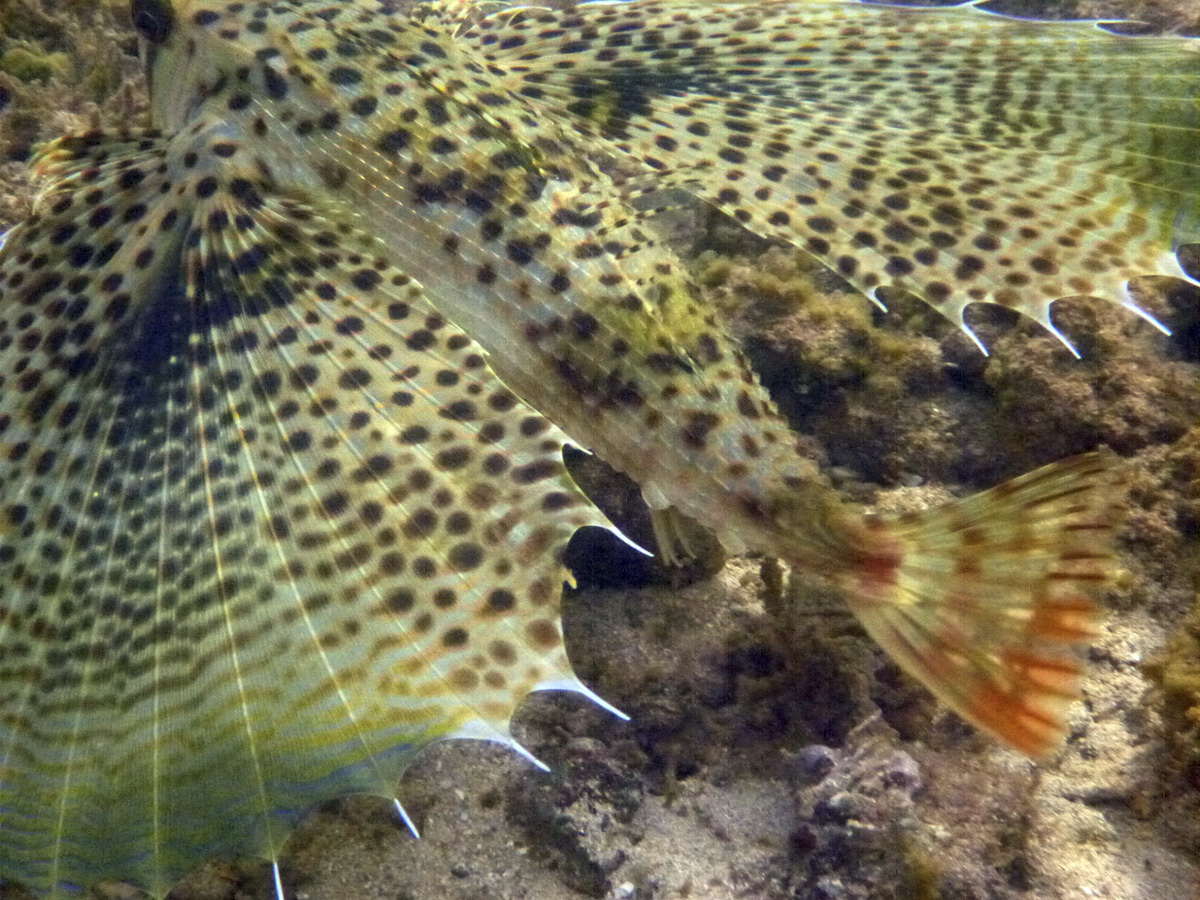

Gurnards feed on the bottom and spread their big fins when threatened.

The downside of this drop-proof system is that it’s hard to remove in the water. So when my young friend Naia, who enjoys photography, wants to borrow the camera, we sometimes get into such mask-snorkel-hair-camera tangles that by the time we make the pass, we’ve lost the fish.

Recently, while snorkeling in about three feet of water, Naia gripped my arm and shouted, “Look!” The fish she sighted was so extraordinary that I lunged for the camera, knocking Naia’s mask and snorkel sideways. Naia had found a flying gurnard.

I’ve seen only seen three gurnards in my life, one in the Caribbean, one off Waikiki and this one on a North Shore reef.

We don’t often see these odd-shaped fish because they like deep water. A University of Hawaii researcher reported in 1973 that 67 Hawaii trawl stations in water 200 to 600 feet deep had caught, as bycatch, 1,322 gurnards.

Gurnards grow to about 15 inches long and occasionally cruise along sandy bottoms in Hawaii’s bays, harbors and shorelines. Of the seven species in the world, only one is found here, but that one has gotten around. The same species lives throughout the Indian and Pacific oceans.

The sight of a flying gurnard is shocking, a piscine version of Green Lantern crossed with Batman. This green-tinged fish with brown spots wears a “cape,” a pair of pectoral fins that, like folding fans, open wide or close narrow.

Underneath the body, two pelvic fins with fingerlike spines hold the fish off the bottom. The spines move like legs, allowing the heavy bottom-dweller to stroll around. The first few forward rays of these fins, pictured above, also move, enabling the walking fish to dig into sand for crabs, snails and shrimp.

While walking, the gurnard usually holds its giant pectoral fins folded at its sides. When the fish is alarmed, though, as ours was when Naia and I followed to take pictures, we see it in all its glory. Threatened gurnards spread their “wings,” greatly increasing their apparent size.

I enjoy my snorkeling dates with Naia immensely. This budding biologist is a marine animal magnet, finding interesting specimens and asking me hard questions. She’s also a good sport, quickly forgiving me when I get overexcited, grab for my camera and nearly strangle her.

Even sputtering and laughing over the camera fumble, Naia and I kept our eyes on the slow-moving gurnard and get some good shots. I don’t know which of us took this picture. But I look forward to our next snorkeling date.