Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

April 7, 2014

Honu is once again moving west through the Society Islands. Although I’m happy to be sailing again, it was hard to say goodbye to Tahiti, with its jagged green mountains, friendly people and perfect french fries. But what I really hated to leave was Papeete’s Marina Taina, a boat basin that made me feel I was floating in a world-class aquarium.

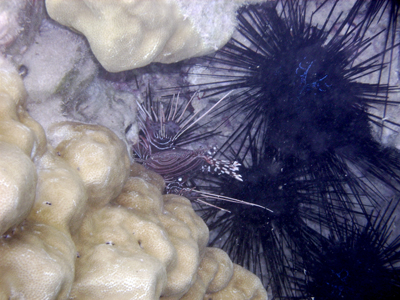

Coral, lionfish, urchin, in the Marina on Raiatea, 2006.

Coral, lionfish, urchin, in the Marina on Raiatea, 2006.

Courtesy Scott Davis

When I was sweaty, tired and frustrated from boat preparations, all I had to do was step from the boat to the pier to get a spirit lift. The rock of the boat and my shadow on the water sent a confettilike shower of fish scurrying for cover. If I waited there motionless, out peeked those busy little color chips to see if the danger had passed. Deciding it had, the fish emerged and went back to grazing.

Boat harbors aren’t usually equated with excellent fish watching because their water is often dark and dirty. Not this one. In most places inside the breakwater, I could see the bottom of the pilings. (I could see fairly deep at night, too, due to the nearby superyachts’ underwater lights.)

But it wasn’t bare pilings that attracted all those fish. The posts and piers that secured our boats looked like candy dishes of marine goodies. With water temperatures 80-some degrees year-round, visibility to 50 feet and daily tides moving water in and out, the conditions in and around Marina Taina are ideal for growth of stony corals.

Stony corals don’t care about boats, people or even floating paper and plastic. All they want is clear warm water, lots of sunlight and a space to stick to. Leave them alone in those conditions and off they go, building the bases of the most diverse and concentrated gatherings of marine life on the planet.

Coral clumps start small. Each head, branch or plate begins as one individual produced by the union of an egg and sperm. Typically fertilization takes place in the water where the parents release their sex cells.

If it isn’t eaten, the fertilized egg develops into a larva that drifts for days or weeks as it matures. When full grown, the tiny pioneer settles down, sticking to one spot where it immediately begins secreting a protective calcium carbonate skeleton around itself.

The coral expands its new homestead by making clones of itself, budding off genetically identical roommates that remain attached to each other. The clones make more clones, and on and on it goes with individuals growing up, out and over one another. As a result, only the outermost layer of a coral head is alive.

All clones in a colony are connected by a thin layer of tissue that allows them to share food. That’s why stepping on, or grabbing, living coral damages the entire colony.

Stony corals get their colors from tiny plants that live inside the skeleton cups. The corals in and around Marina Taina included blue rice, yellow lace, pink cauliflower and brown antler, so stunning it was hard to walk without stopping.

I felt sad saying goodbye to Tahiti with its charming marina full of coral heads packed together like a farmers market display, complete with pushy fish shoppers. My consolation is that more magic lies ahead.