My deceased zebra moray eel, its colors faded in death. ©Susan Scott

February 28, 2021

I love finding dead moray eels. Not that I’m happy they died. It’s just that it’s hard to get a good look at Hawaii’s eels when they’re alive. The ones I see during my swims are either hiding in a hole, or once they spot me, fleeing into one. That’s why when I found a freshly dead zebra moray lying on the ocean floor, I carried it to my kitchen for a close examination.

The body was firm and smooth with a back fin running from behind the head to the tail. I could find no apparent injury. What I really liked about my moray were its little round teeth.

These teeth look like miniature marshmallows but there’s nothing soft about them. The teeth can crush crabs, snails, and human fingers. The forward ones are pointed. ©Susan Scott

These pebble-like teeth are crushers. ©Susan Scott

The reputation of morays as serious biters is correct. Most of Hawaii’s species have needle-sharp, backward-pointing teeth that skewer passing fish, as well as wayward human hands and feet.

If a steel-willed person could manage not to jerk a limb back during a moray bite, the person would end up with puncture wounds rather than the typical slashes. That kind of control, however, is probably impossible, since moray strikes are almost always unexpected accidents.

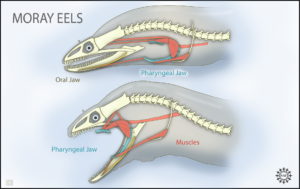

In sharp-toothed morays, as they nab a fish, a second set of teeth in the throat, called a pharyngeal jaw, juts forward, further grips the catch, and drags it to the esophagus where it’s swallowed.

Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation (after Rita Mehta, UC Davis)

But not all moray teeth are sharp. Zebra morays, and their cousins, snowflake morays, have round teeth, ideal for crushing their favorite foods of crabs, shrimp and snails.

Zebra moray hiding. ©Susan Scott

Both species start life as females and later turn into males. Another trait shared by these two is daytime foraging, making them common sights to us snorkelers.

A Zebra moray out and about. ©Susan Scott

This snowflake moray watched me, but did not duck and hide. ©Susan Scott

Nearly all of zebra’s and snowflake’s toothy cousins hunt at night, but I also see them in early morning and at dusk. At sundown on the North Shore, I once saw five moray species at once, each minding its own business in its search for food. I kept my hands and feet at the water’s surface.

When visitors send me photos or videos of what they think are sea snakes, the pictures are most often snowflake morays poking around cracks and crevices for invertebrates.

A snowflake moray hunting mid-morning. ©Susan Scott

Hawaii is loaded with eels. Because their larvae are long-lived, an unusually large number of moray eel species, 42, made it to Hawaii. But we host other kinds of marine eels too. To my surprise, soon after finding the dead zebra moray, I found a dead Hawaiian conger eel, an endemic species. This gave me another chance for a close-up look at an elusive eel.

My dead conger eel. ©Susan Scott

Although conger eels belong to a family separate from morays, congers are also nocturnal, eat fish, and have tiny, but sharp, teeth.

I photographed this conger eel swimming in the open, and unusual sight in broad daylight. The eel soon disappeared under a coral head. ©Susan Scott

Days later, I found a small, dead yellow-margin moray, its identification easy because it is so well named.

The dead yellow-margin moray’s head above; its tail-end namesake below. ©Susan Scott

On a beach at a later date, I picked up another dead moray, just to admire and photograph its teeth. The eel was too far gone to identify the species.

This long dead moray eel, species unknown, had the impressive teeth that give moray eels their undeserved reputation as vicious. The pumping of the jaws is their way of breathing. ©Susan Scott

When Hawaii anglers hook eels, they either throw them back, or let them die on the beach. Large moray eels often contain ciguatoxin, and are, therefore, not safe to eat. Hawaiians named eels puhi in general, and ate some species, including conger eels, called puhi ūhā. Others were considered ʻaumākua, the manifestation of a family god.

After admiring the teeth and forms of the deceased eels, I returned the creatures to the ocean where crabs would eat the bodies, live eels would eat the crabs, and the cycle would carry on as it has for millions of years.

Whether it’s sharp-fanged or pebble-toothed, dead or alive, large or small, I never pass an eel without pausing to admire its snakey shape, pretty patterns, and of course, those amazing teeth.