This model of a male kōlea is 34 years old and counting. (Unfortunately, the artist’s name is not on the stand.) ©Susan Scott

April 5, 2023

At a craft fair in Ala Moana Beach Park in 1989, I found a man selling wooden bird figures. One stood tall and looked like it was wearing a tuxedo.

“They’re called kōlea,” the artist said, when I asked. “That’s all I know.”

That was enough. I loved the piece and bought the carving, a foreshadowing of my future love affair with the migratory shorebirds we also call Pacific Golden-Plovers.

Today, in addition to managing the project called Kolea Count for the Hawaii Audubon Society, and co-authoring a kōlea book with plover expert, Dr. Wally Johnson, I have my own live plover to cherish. For the past five winters, a kōlea I named Jake has foraged in about an acre of grass on the golf course fronting my townhouse complex.

It’s a happy day for me and my neighbors when Jake returns in August. We share the good news and troop outside to welcome the plover home. I breathe a sigh of relief that once more this amazing little bird survived its 6,000-mile round-trip Alaska migration.

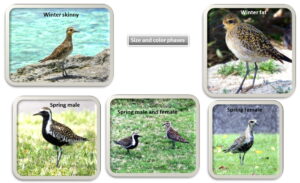

Our Jake, at least 5 years old, is still growing his spring feathers. When complete, his chest and face will be solid black. Females remain speckled. ©Susan Scott

That’s not always the case. Life is precarious for migratory shorebirds. Although the luckiest kōlea live for 21 years or more, their average life span is six-to-seven years. Besides navigating storms, competing for territory, and finding food, predators lurk both summer and winter, north and south.

From August through February, our Jake keeps his distance. After flying 3,000 miles from the Arctic nonstop in four days, he’s tired, thin, and focused on eating anything that crawls: earthworms, cockroaches, centipedes, spiders, and any other creatures people have introduced to Hawaiʻi.

And then comes the spring transformation, a time we kōlea fans all enjoy.

In addition to needing extra nutrients to produce those lovely breeding-colored feathers, our plovers must nearly double their winter weight to fuel their end-of-April journey back to Alaska. Kōlea weigh about four ounces in winter, and about seven ounces when they leave.

©Susan Scott

It’s during this March and April feather-growing, fat-storing time that Jake remembers his human admirers sometimes lend a hand. In March, he starts showing up near our lanais, where several of us toss him bits of scrambled egg, a food rich in fat and protein, two nutrients the birds needs. Some people buy, or raise, mealworms or crickets for their plovers, also nutritious foods.

I use a squirt gun to gently discourage other birds from stealing bits of my microwaved egg offering to Jake. Bird feeding is endorsed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the Humane Society of the United States and other conservation groups. ©Susan Scott

A Red-crested Cardinal, Zebra Dove and Red-vented Bulbul often swoop in for my plover’s egg treats. Jake (upper right) ignores the water squirt, but the other species flee from it. ©Susan Scott

As long as we kōlea fans offer healthy food (no bread or rice), it’s fine in my opinion, and Wally’s, to feed our plovers. More than any other shorebird in the world, Hawaiʻi’s kōlea have learned to coexist with humans, gracing our parks, yards, golf courses, school grounds, and even boulevards’ grassy medians. We’ve altered nearly all of our shorebirds’ natural habitats, and imported hordes of bird predators in cats, rats, mongooses, and barn owls. The least we can do is offer our plovers a little something when they need it most.

Feeding plovers also gives us a connection with wildlife, an association we often miss in today’s urban settings. This explains why so many people worldwide take such pleasure in feeding birds. For those of us who toss egg bits, mealworms, or crickets to our backyard plover, the act is a gift to ourselves as well as the bird.

Our Jake is looking pretty and plump as he nears his departure day the end of April. ©Susan Scott

Since I started the kōlea citizen science project in 2021, I’ve been visiting schools, clubs, and wildlife organizations throughout the state to encourage residents to help us learn more about this special bird. My wooden kōlea goes with me. After all these years, he remains a robust ambassador for a remarkable species.

My wooden kōlea entertaining a class of preschoolers at Trinity Christian School, Kailua. ©Susan Scott