Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

Febrary 8, 2010

Each year, Craig and I travel with a team to Bangladesh to work at an Aloha Medical Mission clinic. The travel time is long and the work challenging, and on the way home we usually stop for a few days of rest in an area of Asia we’d like to see.

Often these side trips involve wildlife, though not Bangladeshi wildlife. Travel in this country is so hard, and tourist facilities so few, I never even tried.

Bangladesh, however, hosts a wonder of the world, a 56,000-square-mile (about Iowa-size) delta called the Sunderbans. This fringe of land and water, shared with India, is where the Brahmaputra, Meghna and Ganges rivers empty into the Indian Ocean’s Bay of Bengal.

A remarkable collection of plants and animals have adapted to life in this fusion of land, river and sea, and our hosts knew their American guests wanted to see them. So this year our Bengali friends kindly arranged a three-day, live-aboard cruise through their Sunderbans preserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

I was thrilled to my toes before we even left the dock. A Ganges River dolphin surfaced for a breath of air right next to our boat.

These dark gray dolphins are harder to spot than oceanic dolphins because they’re only about 6 to 7 feet long and usually swim alone. Also, the little dolphins root in bottom sediments for their fish and shrimp meals, and don’t usually lift snout or tail when they surface.

Calling out “dolphin!” doesn’t work here. You either have your eyes on the water the second that dark gray hump appears or you’ve missed it. Fortunately, the river dolphins appeared throughout the cruise, and everyone got to see them several times.

Ganges River dolphins are blind, their eyes merely pinholes. Because the brackish water in the Sunderbans is thick with the rivers’ gritty sediment and sticky mud, the dolphins find their food using the clicks and clacks of echo-location.

As our boat headed south, I saw what looked vaguely like mongooses leaping daintily along the gray clay bank. The guide informed us that these light-footed, white-faced animals were a family of river otters. A female’s litter of up to four pups stays with her for about a year.

The sleek, brown river otter of the Sunderbans also romps all over Europe and Asia, ranging from the Arctic Circle to Indonesia and from Ireland to Kamchatka.

River otters can live in salt water but must find fresh water to clean their fur. This is easy in the Sunderbans where during the summer monsoons, river flows overpower ocean tides and the water becomes fresh.

As the boat moved up and down the forest’s capillaries, we spotted macaque monkeys digging crabs from their holes on the beach, watched gray-headed fishing eagles pluck fish from the surface and observed countless axis deer (the same species we have here in Hawaii) grazing in the mud-floored woods.

For bird lovers the Sunderbans is paradise. We could barely pass the binoculars fast enough to marvel at blue kingfishers, golden woodpeckers and giant storks.

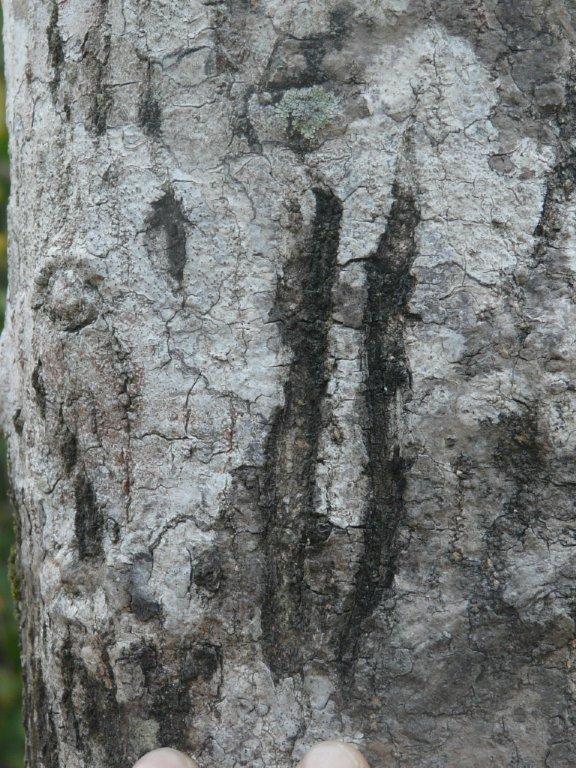

On a hike our guide pointed out long, deep claw marks on the tree trunks Bengal tigers use as scratching posts. The tiger and the other big predator that lives in this area — the saltwater crocodile — stayed out of sight during my visit, but that’s OK. I know they’re there.

I’ve been going to Bangladesh for 13 years now, and the mention of it conjures up a lot of images for me. Wildlife was never one of them. Now it is.