My beached Lanikai flatfish. ©Susan Scott

December 31, 2020

My year of writing about marine animals ended on a high note when I found a baby flatfish on Lanikai Beach. The inch-wide roundish disk glistening in the sun looked like a piece of plastic from inside a bottle cap. When I picked it up, though, it wiggled. Craig and I found a paper cup, filled it with seawater, and carried the treasure home.

As I experimented with backgrounds to photograph the transparent youngster, I recalled three similar flatfish I found washed up on the rocks near the Kailua boat ramp. It was 1985, a year I remember well given that I had just graduated from UH, and Craig and I were preparing to sail our new boat, “Honu,” moored in Connecticut, home to Hawaii.

In this soupspoon, both eyes are clearly visible above the mouth. ©Susan Scott

The fish’s bulgy eyes are clearly visible against a black background. ©Susan Scott

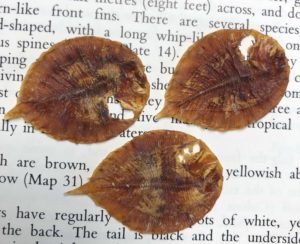

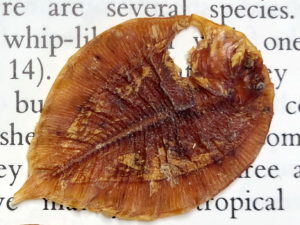

The three little Kailua fish were so remarkable, and so flat (and so dead), that I pressed them in a book I had recently bought called Sea Watch, The Seafarer’s Guide to Marine Life, by Paul V. Horsman, 1985.

This week, I found the musty, water-stained book in my home library, riffled the pages, and out fell those 35-year-old flatfish, brown, crispy, and amazingly intact.

Found on a lava rock, 1985, and pressed in a book. ©Susan Scott

After all these years, this fish’s eyes are still visible on the top, right. ©Susan Scott

Flatfish are a group of about 800 species ranging from the Arctic to the Antarctic. All flatfish are, well, flat, their matlike bodies ideal for lying on the ocean floor, waiting to ambush a passing fish or invertebrate.

In some parts of the world, flatfish are major fisheries. The Northern Atlantic and Northern Pacific oceans host halibut, the largest of the flatfish, growing to 8 feet long. Halibut don’t reproduce until they’re eight years old, and the fisheries are regulated to maintain healthy populations. Other flatfish caught for food are flounder, plaice, turbot, and sole.

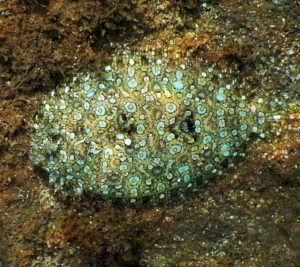

Hawaii waters host at least 18 kinds of flatfish, 15 flounders and 3 sole. Flowery, also called peacock, flounders (Bothus mancus) are the largest, growing to 20 inches long. Panther flounders (Bothus pantherinus) grow to 12 inches long. Hawaii’s other flounders are only several inches long. The three sole species here are also small, ranging from 2.5 to 5 inches.

This panther flounder was following a box crab, a ploy some flounders use for finding invertebrates startled, or dug, up by other species. I’m guessing this is a panther flounder, based on the proximity of the two eyes, but it’s hard to tell from the similar flowery flounder. Waialua. ©Susan Scott

We have no commercial fishery for flatfish, but spearfishers stab and eat our largest, the flowery flounders. Hawaiians named all flatfish pāki’i, meaning flattened or spread out flat.

A flowery flounder, Bothus mancus, Hanauma Bay. Photo courtesy David Schrichte.

The ones I see most often on Oahu’s North Shore are flowery and panther flounders. These two are hard to tell apart, because both change colors and patterns almost instantly to blend in with their backgrounds. The distance between the eyes is a feature to note. Flowery flounders’ eyes are further apart than the panthers’ eyes.

This is either a flowery or panther flounder. Both change colors and patterns instantly. Waialua. ©Susan Scott

Eyes are a remarkable part of all flatfish, because they are both on the one side of the head. Flatfish start life as normal-looking fish, with one eye on each side. As they mature, though, the fish grows flat as a pancake. Since flatfish lie on the ocean floor, an eye on the underside would be useless. Nature took care of that in an unusual way, the lower eye gradually migrating, as the fish matures, to the top side to join the other.

Photographer, Russell Gilbert, labeled this a Thompson’s flounder, one of Hawaii’s 13 flounder species. Thompson’s flounders grow to about 5 inches. © Russell Gilbert

I don’t know the identity of my four tiny flatfish, but they look like the same species. My guess is that they’re an immature stage of one of our three soles.

The location I chose to save my three flatfish in 1985 is significant because Sea Watch was my inspiration for the “Ocean Watch” column I created for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 1987. Now, all these years later, I’m once again inspired by finding a beached flatfish alive, and then discovering its three preserved kin in the book that motivated me to write about the subject I love.

Published in 1985 by Facts on File, New York.

After shooting pictures and a short video of my lively little fish, https://bit.ly/2Lg2Baf I took it to the Kailua boat ramp and returned it to the ocean. It felt like a good start to a new year.