While kayaking in Midway’s lagoon, seabird biologist Luke Halpin, found this glass ball afloat. ©Craig Thomas

March 18, 2021

“Glass balls bring out the worst in people.” This was the conclusion a U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist came to after working at Midway Atoll. She and I had been discussing a volunteer who ditched work to sneak onto off-limits beaches (monk seal resting sites) to collect glass balls, leaving his fellow volunteers angry and ball-less.

The lower float is known as a rolling pin. Glass balls are mostly green because they were made from green recycled sake bottles.

The bottom of each glass ball has a plug, or sealing button (shown.) Some bear symbols of the glass factory that made the float. Mine have no such manufacturing marks, considered valuable to some collectors.

I could see her point. After working on, and sailing to, dozens of remote Pacific islands with glass balls on beaches, I’ve witnessed some pretty bad behavior in otherwise good people. (I’m reminded of the gulls in Finding Nemo shouting, “Mine! Mine! Mine!”) More often, though, I remember the times when these pieces of glass garbage brought out the best in people.

Yes, garbage. According to author Walt Pich, in his 2004 self-published book called, Glass Ball, A Comprehensive Guide for Oriental Glass Fishing Floats found (sic) on Pacific Beaches, the glass floats we so love to find are gomi, (garbage) to most Japanese fishermen. As Pich sifted through wrecked boats and vacant sheds looking for discarded glass balls, fishers often called friends who laughed and shook their heads over the crazy American so delighted with their trash.

Pich found, and photographed, piles of dusty glass balls, some heaps numbering in the thousands. Today, where nearly indestructible plastic floats come with holes and handles for securing ropes and nets, smooth glass buoys aren’t practical to anglers. Besides being breakable, glass floats need hemp, jute, or cotton nets to hold them in place. When those wear out in sun and surf, the floats drift away.

Fellow volunteer workers and I at Midway collected lost plastic fishing floats from the beach to define a walking path. These are more practical to anglers than glass, but not usually collectors’ items.

To those of us who consider these orbs treasures, that’s a good thing. Even better, is when the netting is still intact on the ball.

Luke Halpin spotted this glass ball from a research vessel off British Columbia. The captain stopped the ship to retrieve it. Photographer unknown.

This was a gift from the commanding officer at Midway when the atoll was a U.S. Navy base. The special float has a place of honor in our living room.

This thrill comes in different ways for different people. Years ago, while standing on the roof of the former barracks on Tern Island in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, three of us workers spotted a large glass ball drifting toward our windward beach, its net covering intact. Already possessing such a treasure, two of us told our young volunteer to go for it.

About an hour later, she returned to the roof empty handed. The underside of the net had so many living animals on it that she couldn’t bear to kill them. Instead, she carried the netted ball, its goose-necked barnacles waving their brown feet and offshore crabs scurrying for cover, to the tiny island’s leeward shore and set it adrift. Lose the ball; save some lives.

Another display of generosity occurred at Midway last year when one of the Fish and Wildlife biologists found an 18-inch glass ball, the largest ever made in Japan for fishing buoys. Because she knew that a student volunteer had not found one, and never would once she returned to her Midwest home, the kind biologist planted the ball on a remote part of the beach where the student jogged each day.

We all shared the student’s joy as she showed off the huge glass ball she found during her morning run. The few of us who knew what a true gift it was, kept the secret.

A lifetime of working on, and sailing to, remote Pacific islands has made Craig and I rich in glass balls. The top two were gifts. In that spirit, I’ve also given some as gifts.

I bought this wooden turtle dish while working in the Philippines with the Aloha Medical Mission. It became the perfect glass ball container.

Even broken pieces of glass balls have their uses.

I used glass ball pieces found over years on beaches in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands for the feet of this commissioned art piece. The cigarette lighters are from albatross nests, blue chips and wood from Oahu beaches. Clouds are discarded operculums from helmet snails eaten in Tahiti. (Brown Booby Bird, 2020.)

It’s interesting that glass balls are viewed as so much junk by Japan’s fishers, yet are so coveted by people on the opposite side of the Pacific. At their best, these orbs are like crystal balls that carry a message. For each of us, that message is our own to imagine.

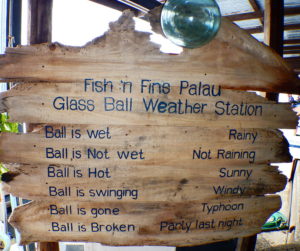

The dive shop operators in Palau used their imagination to give their glass ball meaning. ©Susan Scott