Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

June 11, 2016

HOOK ISLAND, GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK >> While snorkeling here this week, I found myself thinking that there’s too much coral.

Capt. Cook thought so, too, in 1770, and he didn’t even know that the lagoon he was exploring was a vast channel paralleling the Australian mainland.

The concept of a barrier reef forming a passage came later. The open stretches of this so-called passage are about 100 feet deep. But sprinkled among them are coral-rimmed islands, free-standing reefs, atolls and peaks. Some reefs are visible, but many lie just below the surface.

Today we have GPS charts that point out most of them. But not all. Last week I came within yards of crashing Honu, at speed, into a tiny, uncharted pinnacle.

“Turn right!” Craig shouted from the bow. We avoided disaster only because he was securing the anchor and saw waves breaking ahead.

Today, corals are much loved and a frequent topic in discussions of global warming. But in the early years of exploration, no one knew what they were. Eng-lish Capt. Mathew Flinders speculated that corals were “animalcules” that lived on the ocean floor.

When they died, other animalcules (love that word) grew atop, and so on, thus building “a monument of their wonderful labors.” The creatures’ care in building their walls vertically was to Flinders a “surprising instinct.”

What he didn’t know was that stony corals grow upright because they host algae that need sunshine to survive. That fact came to light 30 years later from another explorer, Charles Darwin.

My problem with the corals here isn’t running the boat into one of their “monuments” (although I’m more watchful now), but that I can’t take them all in.

The corals on these reefs look like mushrooms, wheat fields, brain tissue, antlers, cabbage leaves, chicken skin, grassy knolls and endless other shapes, colors and textures.

Some corals are hard; some are soft. Many cover their space like rugs; others wave greetings like anemones.

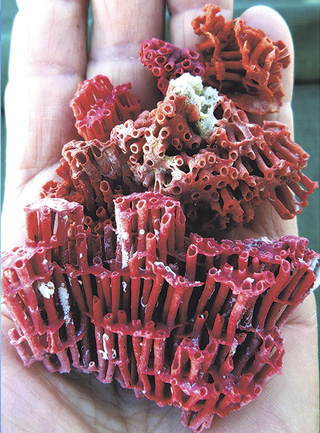

Among all the coral splendor here, one in particular stands out for me. On a white-sand beach I found pieces of a bright red structure of tubes known as organ pipe coral. In admiring the tiny pipes, which remind me of fairy castles, I’m in good company. Capt. Cook’s naturalist, Joseph Banks, wrote about being overwhelmed by the variety of corals, too, especially one he called Tubipora musica. That’s the scientific name of my organ pipes.

It’s clear to us modern sailors that this labyrinth of coral shoals must have been a nightmare to early explorers. It’s also clear why mariners, past and present, admire them so. What other animalcules build monuments?