Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

February 16, 2015

Port Angeles, Wash. » While spending a few days in this town on the Olympic Peninsula, my friends took me to the Feiro Marine Center, where I fell in love with a giant Pacific octopus named Obeka.

“Giant” is part of the animal’s common name because this North Pacific species is the largest in the world. Adults grow to 110 pounds and, when spread out like an umbrella, can measure 20 feet across from arm tip to arm tip.

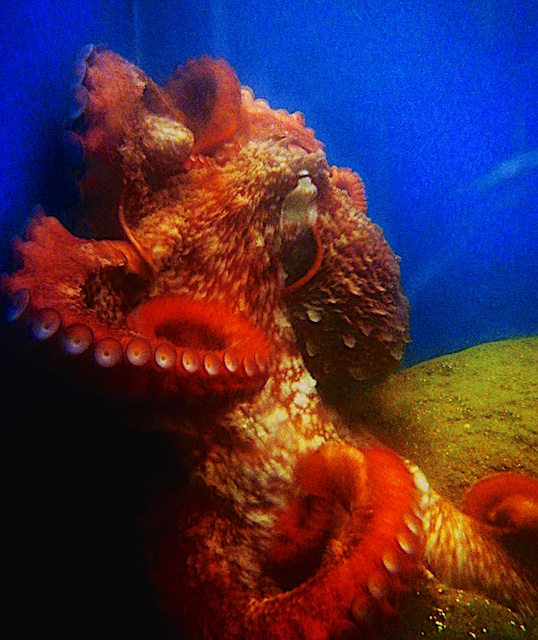

This female octopus isn’t fully grown.

She weighed 1 pound when brought to the center a year ago. Now she weighs 35 pounds with a span of nearly 7 feet.

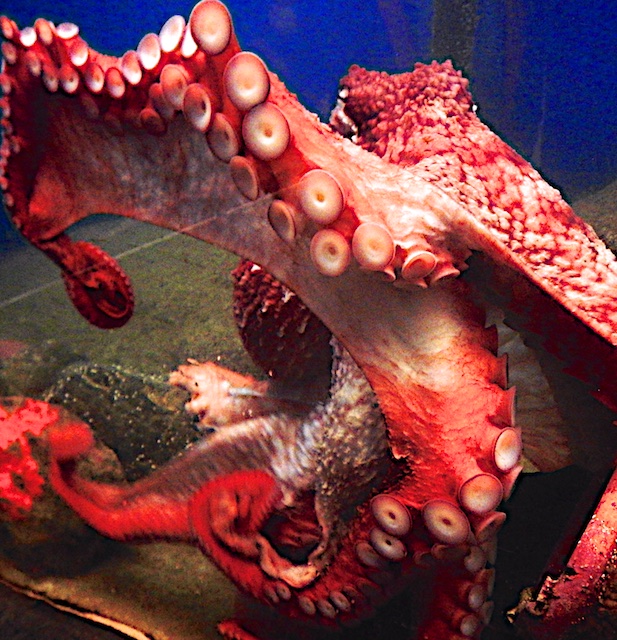

Obeka is a striking life form. When I first saw the vivid-orange octopus, she was resting, her head hidden behind huge suckers stuck on the aquarium glass.

A giant octopus has about 1,600 suckers. The largest on an adult are 2 1⁄2 inches across and can support about 35 pounds each.

The outer edge of the sucker contains ridges that help prevent slipping when clamped down. Muscles control the shape of the inner wall, creating the suction force for each individual sucker. But these suckers do more than suck. They taste what they touch.

With hundreds of round “tongues,” the octopus can hunt in total darkness and find food under rocks and in cracks.

Food in this case is anything the creature can catch, including birds. A giant octopus once astonished Washington state ferry workers by hiding under a rock near the terminal.

When a gull landed on the exposed surface at low tide, a suckered arm appeared from below, grabbed the unsuspecting bird and hauled it below for a meal.

The stories about giant octopuses slithering out of covered aquarium tanks to go hunting in a neighboring tank are true. Even though the boneless animals look like slimy blobs out of the water, their muscular arms and suckers still function on dry surfaces and can pull the body along for short distances.

Obeka so impressed me that I bought a book about giant octopuses. After reading a bit and chatting with the center’s workers, I revisited Obeka’s tank to tell her how extraordinary and beautiful I thought she was.

As if hearing me, she woke up, looked at me with intelligent eyes and crawled around her tank seemingly posing for pictures.

Before Obeka grows to full size, the marine center will return the potential mother to her ocean home to reproduce. She’ll die soon after her 68,000 eggs hatch (giant octopuses live about four years), but she will have left more than baby octopuses. In saying hello to a writer who can share the glory of the giant Pacific octopus, she has helped people appreciate these remarkable animals. Your species thanks you, Obeka. As does ours.