Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

June 13, 2008

Life can be hard for turtles, even the ones Hawaii honu lovers watch over, tend to and track.

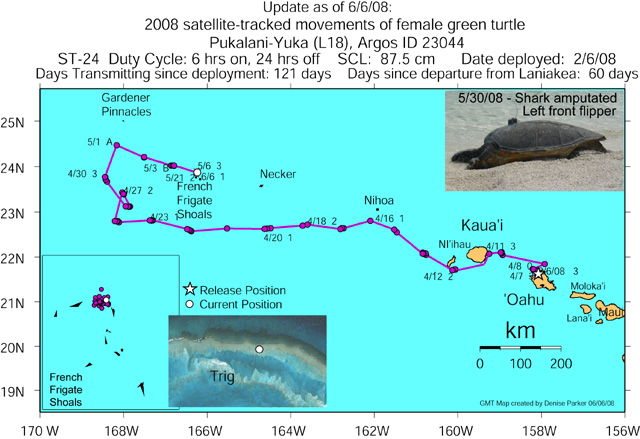

The green turtle Pukalani, otherwise known as L-18, had a particularly hard day May 30 when she lost her left front flipper, likely to a shark. I say likely because turtles sometimes lose flippers to derelict fishing lines and nets when these tough materials wrap around a flipper and strangle it.

This, however, was a sudden, clear-cut injury, the trademark of a tiger.

These sharks are especially active this time of year in Pukalani’s current neighborhood, French Frigate Shoals in Hawaii’s northwestern chain. Large tiger sharks cruise the lagoon looking for fledging albatross chicks. When a chick flounders and rests on the water, the shark swallows it.

In this sharky process of natural selection, turtles are also targets.

Pukalani is in the spotlight right now because she’s one of the regulars at the North Shore’s Laniakea. In the late 1990s a group of turtles began sleeping on the beach there, and they have since become stars. These baskers provide a rare opportunity for residents and visitors to see wild turtles out of the water.

A team of dedicated volunteers take turns looking after the napping turtles and answering questions. This goes on seven days a week, year round.

L18 (Pukalani) with satellite tag at Laniakea before departure.

Photo by Katie Starling – April 3, 2008.

I’ve done some turtle-sitting at Laniakea, and it’s easy to view these docile creatures as pets. These are wild animals, though, with a crucial and dangerous mission: perpetuate their species.

In spring, some of these turtles head to the open ocean to swim to their French Frigate Shoals nesting grounds, about 500 miles northwest of Oahu. Both male and female green turtles migrate there to mate and nest, but they don’t do it every year.

No one can tell which turtles are taking a year or two off, but in February, turtle biologist George Balazs and his assistants made their best guess and fitted satellite tracking tags on three Laniakea females. The researchers hoped to follow the turtles’ journeys.

Of the three, only Pukalani felt the urge. She left in April and the biologists mapped her progress.

The turtle overshot her goal but then corrected her error and arrived in the atoll 29 days after leaving. Then she had her run-in with the shark.

Flipper amputations are common among sea turtles. Usually these injuries aren’t fatal, and they do not stop the turtle from laying eggs. Turtles missing front flippers have nested successfully year after year.

I knew Pukalani’s story when I went snorkeling at Shark’s Cove last weekend. As I floated over a turtle, I paid attention to the powerful strokes of its front flippers. How one-flippered turtles swim 500 miles, haul themselves high on the beach and then return 500 miles to Oahu is a miracle of nature. The turtles’ navigational abilities are equally amazing.

Everyone is rooting for Pukalani to lay her eggs and return to Laniakea. Balazs is optimistic. “I have every reason to believe that L-18 will fulfill her species and ecological role by completing her egg laying to perpetuate Hawaii’s green turtles,” he e-mailed us honu fans. “And that’s what wildlife populations are all about.”

L2 (Hiwahiwa) – stayed at Laniakea. Photo by Scott Davis, taken May 18, 2008.

L2 (Hiwahiwa) – stayed at Laniakea. Photo by Scott Davis, taken May 18, 2008.

L1 (Brutus) – missing half of left rear flipper. Photo by Scott Davis.

L1 (Brutus) – missing half of left rear flipper. Photo by Scott Davis.