Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

August 19, 1996

Last weekend, while visiting my sailboat in the Ala Wai Boat Harbor, I saw a group of fishermen standing around in knee deep water. Each held a small fishing pole which he jerked up and down with great concentration. When I looked into the nets fastened to the men’s waists, I saw dozens of silvery little oama.

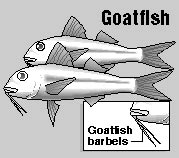

Oama are juveniles (7 inches or less) of the goatfish known in Hawaii as weke.

Weke have one or more stripes running the entire length of the fish’s body. Four of Hawaii’s nine native species of goatfish are called weke, some with variations such as weke’a, weke-ula, or weke pueo. Common English names for weke are white goatfish, yellow goatfish, orange goatfish and bandtail goatfish.

Weke are mostly inshore fish but newly hatched weke head offshore to feed on plankton. When the fry are 3-4 inches long, they cruise back in schools, usually in August, searching for shrimp, worms and other invertebrates along sandy bottoms.

Goatfish search for food by stirring up the sand with wiggly chin whiskers called barbels. Goatfish get their name from these chin whiskers, which leave little puffs of sand clouds in the fishes’ wake.

Since the fish taste their food first with their barbels, alert anglers can sometimes hook oama under their chins rather than in the mouths. Oama are crazy for shrimp, a common bait, but also bite on pieces of fish flesh, including other oama. Each angler can keep 50 oama per day.

Anglers like to catch these small goatfish for several purposes. One is to use them as bait for catching papio (young ulua or jacks), which come inshore during this time to feed on oama. One fisherman told me oama is the master bait for papio, but the oama must be kept alive.

Others prefer to eat their oama. Another fisherman told me that you scale the fresh fish, remove the entrails and gills, dip the fish into your favorite batter, then fry with the heads on.

Some people eat oama raw after salting them.

No illnesses have been reported from eating oama, but the same is not true of some adult weke. Weke’a, weke pueo and some mullets have been implicated in a poisoning that causes temporary illness with hallucinations.

This poisoning is relatively rare. In 1994, three cases were reported; 1995 had only one case; 1996 has had two cases so far. Hallucinatory fish poisoning is most common in the summer months, occurring in fish caught near Molokai, Kauai and Oahu.

No one knows why this poisoning occurs, but the toxin appears to be concentrated in the heads.

To be safe, don’t eat the heads of mullet and weke caught near Molokai, Kauai or Oahu in June, July or August.

Symptoms develop in five to 90 minutes. These are tingling around the mouth, sweating, weakness, hallucinations and chest tightness. The toxin affects some individuals during sleep, producing vivid nightmares. Because of this, some call the band-tailed goatfish “the nightmare weke.” Hawaiians called this same fish weke pahulu (chief of the ghosts).

Victims hallucinating, or extremely depressed, should go to an emergency facility for help. Others should remain calm and wait until symptoms disappear, usually overnight.

Save any remaining fish for analysis. Report all cases to the State Department of Health.