Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

March 4, 2013

Why is it that tons of people and organizations are not trying to catch as many crown of thorn starfish as possible as we learn that the great reefs are greatly endangered by them?” wrote an unidentified reader last month. “Isn’t there a bounty or something … at least in Australia? Should be.”

The crown-of-thorns starfish isn’t the demon it has been made out to be. Native to all coral reefs throughout the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the species plays an important role in keeping the reefs healthy.

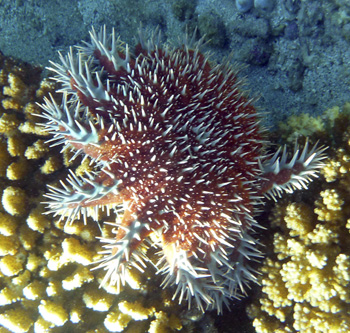

Crown-of-thorns starfish.

Crown-of-thorns starfish.

©2013 Susan Scott

I know. After all the negative press this starfish has garnered, that sounds wrong. But like forest fires, which play a cruciasl role in woodland ecosystems, the crown-of-thorns starfish is a key player in coral reef biodiversity and succession.

Crown-of-thorns starfish prefer to eat branching and table corals. After the starfish finishes its meal, it moves on, leaving the coral skeleton exposed for other species to settle on. Hosting a variety of plants and animals makes the reef less vulnerable to pathogens and predators that target particular species.

At its normal low density on a coral reef, the crown of thorns is a good thing. It’s when the starfish multiplies at a rate greater than normal, and the reef is losing more coral than usual, that the dilemma arises. Should we dive in and kill as many individuals as we can? Or should we step back and let nature take its course?

The problem is that we don’t know whether this is nature taking its course. One theory holds that fertilizers and wastes from human activities cause starfish blooms.

But whether an outbreak is natural or not, will killing starfish do any good?

The jury is out. Some researchers believe that killing the starfish is a waste of time and money. It will multiply and eventually die off regardless of what we do.

In one study in Tanzania, however, researchers removed the starfish from one reef during a bloom, and did not in two others. Coral in the removal reef did better.

The National Park Service is going with this tactic. Divers in American Samoa recently removed 90 starfish from a reef there.

A theory for the increase in Samoa’s starfish is that the 2009 tsunami that hit the islands exposed nutrients (natural or not) previously settled on the ocean floor. The hypothesis works time-wise because it takes about three years for the starfish to reach sexual maturity.

Whatever causes crown-of-thorns blooms, there is no bounty on them, nor should there be. If you see a one while diving or snorkeling, do what I do: Marvel over the form and function of these remarkable creatures, and appreciate the complexity of coral reefs.