JCNWR: A place for birds and people who love them. A shelter inside the refuge. Susan Scott photo.

March 3, 2023

Last week, I visited the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge, a haven to Hawaiʻi’s wildlife, and a mystery to Hawaiʻi’s residents. Well, a mystery to me. Every time I pass the sign during my North Shore excursions, I have questions. Is this a natural wetland? A wastewater treatment plant? Are the ponds from the sugar industry? Do birds and turtles nest here?

Now that I’ve recently had an official tour by U.S. Fish and Wildlife volunteers and birders, Dick May and Pete Donaldson, I have answers to my drive-by questions: yes, to all of the above.

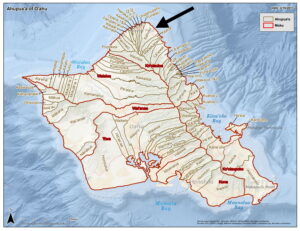

The current JCNWR lies in the Kahuku ahupuaʻa, the Hawaiian term for a pie-slice division of land that extends from mountain to ocean. Ancient Hawaiians surely used the area’s lower spring-fed wetland area to grow crops, raise domestic animals, and harvest birds and turtles for food.

Signs along Kamehameha Highway designate ahupuaʻa boundaries, marked in ancient Hawaiʻs with stone heaps.

In 1890, the Scots-Irish sugar baron, James Campbell, forever changed the lower wetland part of the ahupuaʻa by starting the Kahuku [Sugar] Plantation, and building settling ponds in the marsh. Settling ponds allow solids in wastewater to drop out, or settle, to the bottom. Kahuku plantation closed in 1971.

Because Hawaiʻi’s endangered waterbirds fed and nested in the area, in 1976 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service leased, and later bought, the former wetland from the Campbell Estate. The purpose of the purchase was to protect and manage the region for the federally-protected birds that frequented the place. Sea turtles also lay eggs in sand nests on the bordering beach.

A sign on the entry road.

In 1980, the City and County of Honolulu built the Kahuku Wastewater Treatment Plant to serve the town of Kahuku. Because the wastewater facility shares the entrance road with the refuge, this is the first structure you see when driving in at the JCNWR sign.

The gate to the refuge is locked. On the right is part of the wastewater treatment facility.

One reason it’s unclear what’s going on here is because it’s a closed refuge, a designation that protects one of the few remaining nesting sites for Oahu’s waterbirds, seabirds, and sea turtles.

Another reason the area may be confusing is the presence of adjacent former shrimp farms. Some of these smaller ponds, visible from the road, are failed attempts at shrimp aquaculture on private land. The shrimp sold in the roadside restaurants there are imported. The Romy’s menu also offers tilapia. A worker there told me these fish are grown in the ponds.

One of the aquaculture ponds visible from the road.

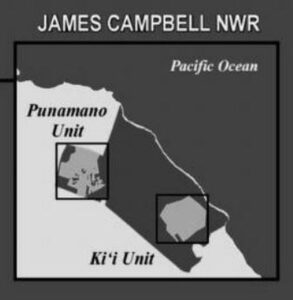

The James Campbell refuge, totaling 1,100 acres (about 1.7 square miles) consists of two areas. One is the larger Punamano unit that contains a spring-fed marsh and upland grassland and shrubland, safe from rising sea levels. Researchers only work in this area where a predator-exclusion fence protects translocated seabirds and their chicks from cats, rats, mongooses, and dogs.

The smaller Kiʻi unit contains several of the former shallow-water sugar mill settling ponds. Federal managers use water control systems to maintain depths for ideal feeding and nesting habitat. The invasive aquatic plants that thrive here need continual mechanical clearing to maintain open water.

The USFWS offers guided tours near the Kiʻi Unit on Saturdays from October through February, when the birds are not breeding. But from March through September, the place is for birds only.

During our walk, we found along the edges of the former sugar settling ponds, countless shrimp and snail shells, discarded by the migratory shorebirds after eating the soft body parts. Our guides called these animals crayfish and apple snails. I knew these were not native species, and wondered where they came from.

Half-eaten crayfish carcasses litter the grass at the pond edges. Bristle-thighed Curlews love them. Susan Scott photo

Crayfish are freshwater versions of lobsters. The crayfish in the refuge are red swamp crayfish, also called ʻopae pake, scientific name Procambarus clarkii. Native to the rivers, lakes, and swamps of the southern U.S. and northern Mexico, the hardy little freshwater creature is now found in all inland waters of all continents except Antarctica. The species grows 4-to-5 inches long, and is raised worldwide as food, bait, aquarium pets, and laboratory research animals.

The first red swamp crayfish were introduced from California into taro patches on Oahu in 1923. In 1937 the crayfish were transplanted from Oahu to Maui and Hawaii Island. By the 1940s, the adaptable crayfish, which can flourish in water clear-to-murky and fresh-to-brackish, were found throughout the main Hawaiian Islands.

From a USGS website about red swamp crayfish.

Apple snails, South America natives, were introduced to Hawaii as a food crop, and are for sale in aquarium stores. Although the round snails can grow to the size of an apple, the ones in Hawaii are about golf ball size. Today, apple snails are found on all islands except Molokai and Lanai.

Apple snails, Hawaiʻi Division of Aquatic Resources photo.

Apple snail eggs along a Waialua waterway. Susan Scott photo

Because they harm taro plants, eat native species, and damage freshwater habitat, both the red swamp crayfish and apple snail are considered invasive pests in Hawaiʻi — by us humans. Our shorebirds consider them gifts of the best kind: abundant protein in easy pickings.

The JCNWR was never a mystery to Hawaiʻi’s shorebirds and waterbirds, and now, because of a tour (thank you, Dick and Pete) and some homework, it’s not nearly the mystery to me that it once was. But there’s so much more. As I read this over, I realize I’ve barely written anything about the birds that people work so hard here to protect. In researching this piece, for instance, I learned some amazing facts about our Bristle-thighed Curlews. But that’s for next time.