Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

June 16, 2018

As much as I loved swimming with millions of lovely, pulsing salps last week, their gelatinous bodies obscured the hard and soft corals below. In addition, it’s winter in the Southern Hemisphere, and even in tropical Queensland the water and air felt cold. I moved on, swimming hard to get warm and to see some of Australia’s famous reef.

I didn’t get far. As soon as the water cleared from the salp assembly, another first for me appeared: a gorgeous flatworm swimming for all it was worth in midwater.

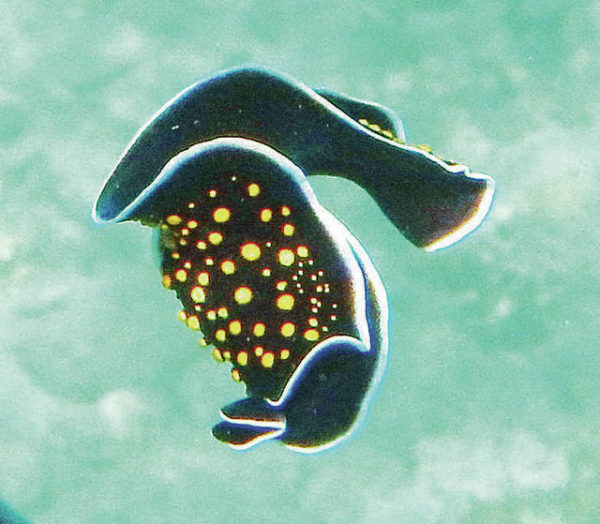

A flouncing flatworm, scientific name Thysanozoon nigropapillosum.

A flouncing flatworm, scientific name Thysanozoon nigropapillosum.

Flatworms are common in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

©2018 Susan Scott

Most of us think of worms as tube-shaped, but the ocean hosts a worm group that rivals butterflies in grace, color and patterns.

Flatworms live up to their name, their bodies being so thin and spread out it’s hard to imagine the animals have innards. But guts they have, including muscles, digestive systems, sense organs and gonads. They’re simply laid out in branches.

Some flatworms creep around the ocean floor by beating microscopic hairs on their undersides. Others, such as the one I saw, swim using muscles to flap the body edges, the result being a worm version of a flamenco dance.

I have often found flatworms shuffling around coral reefs, their tissue- thin bodies conforming to the nooks and crannies they pass. This, however, was the first time I’d seen one out in the open going somewhere.

The paper-thin creature flapping its ruffled edges looked vulnerable out there in the water column, but the worm had little to fear. Flatworms’ bright colors and patterns are a warning to fish: Don’t eat me, I may be poisonous.

Some flatworms carry tetrodotoxin or other marine poisons, and some just pretend to carry it. The fakers resemble toxic nudibranchs (sea slugs), gaining protection through mimicry.

The fancy-dancing flatworm entertained me for as long as I could stay in the cold water, but when I returned to the boat, a surprise awaited me. Two readers had sent email links identifying the disappearing blue dots that have baffled me for years, nicknamed “mermaid fairy mist” by another reader.

The flashers are male copepods, scientific name Sapphirina, common name sea sapphires. Copepods are shrimplike animals at the base of the marine food chain, present nearly everywhere. Most species are so tiny they’re barely visible.

We snorkelers, divers and plankton collectors notice male sea sapphires only when they turn on their extraordinary lights, purpose unknown. When turned off, the creatures are nearly undetectable.

Sapphirina females don’t flash, but have enormous eyes compared with males, and live inside salps. Perhaps the females look through the windows of their crystal carriages searching for Mr. Right.

Check out the fantastic sea sapphires at goo.gl/1jaUy5.