Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

April 15, 2017

Decades ago, when Craig and I boarded a friend’s boat in the Ala Wai Boat Harbor, the crackling sound below deck made us wonder if the boat was falling apart. I later learned that the big noise comes from a small package: 1-inch-long snapping, or pistol, shrimp.

We oceangoers rarely see the little gunslingers because they live in burrows. But we hear them. The split-second closure of each shrimp’s single, oversize claw makes a popping sound. When the creatures pop by the thousands, as is often the case, it’s like snorkeling in a giant bowl of Rice Krispies.

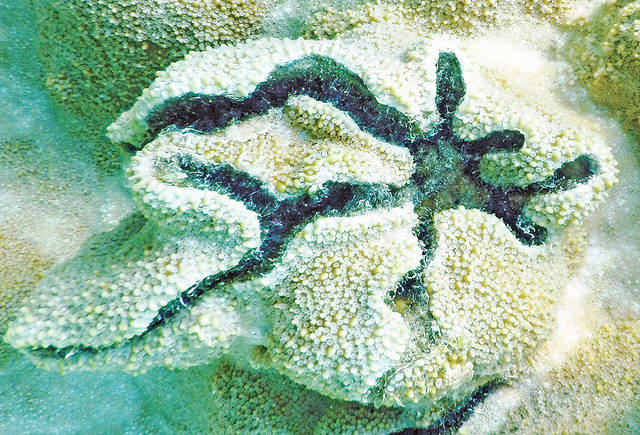

Petroglyph shrimp channels are etched in lobe coral off Lanikai Beach.

Petroglyph shrimp channels are etched in lobe coral off Lanikai Beach.

©2017 Susan Scott

The crackling is so loud that submarines can hide among shrimp colonies and go undetected by sonar.

The shrimp snaps for food, sending out a bubble bullet that stuns passing prey. The snaps can also be warning shots to trespassers, and perhaps a come-on to members of the opposite sex.

Most snapping shrimp dig, and live in, mud or sand burrows. We rarely see these basement apartments because they’re under rocks and rubble. One kind, though, lives in exposed sand burrows guarded by a pair of gobies. The shrimp digs while the fish keep watch. When a predator or curious snorkeler gets too close, the team dives into the hole together.

Other snappers, called petroglyph shrimp, set up housekeeping in living coral heads by making channels. No one knows how the shrimp creates the cracks. Either the animal is able to inhibit coral growth at the chosen site, or that big claw is an all-purpose tool that, in addition to firing lethal bubbles, can also dig.

Petroglyph shrimp (usually Alpheus deuteropus) create wavy, U-shaped crevices, the largest about a quarter-inch wide and 10 inches long. These are not the shrimps’ burrows, but rather boulevards lined with crops and cops.

The crops are seaweed, veggie meals for the shrimp. The cops are white hydroids, stinging jellyfish relatives that look like tiny trees. The hydroids protect the lane but might also eat the shrimps’ babies when they hatch. Security guards don’t come free. Gobies are carnivores, too.

The deepest parts of petroglyph channels bear cul-de-sacs that precisely fit each shrimp’s body. When it’s threatened, the shrimp retreats to its den, blocking the entrance with its large claw. Channels 2 inches or less usually house a single resident. Longer ones can accommodate two to four shrimp, each with its own separate burrow.

Hawaii’s petroglyph shrimp have pink eyes encircled by red dotted lines. The bodies are transparent with red surface dots.

So they say. I’ve not seen one. But I often see, and stop to admire, the shrimps’ plant-lined streets with twiggy sentries. The neighborhoods deserve a feature in Better Homes and Gardens.