Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

June 22, 2019

Retired marine biologist Bruce Mundy emailed that he enjoyed last week’s column on eels, and kindly pointed out my error in writing that Franz Steindachner named the Steindachner moray after himself. Bruce wrote that “naming a species after oneself is considered unethical.” In a search, Bruce found “an astonishing 59 species and 5 genera” that taxonomists named after Steindachner.

There are strict rules in taxonomy, the science of classifying and naming organisms. Because Latin was the language of Western European scholars in the 1750s when Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus introduced the two-name system, all terms were, and still are, in Latin.

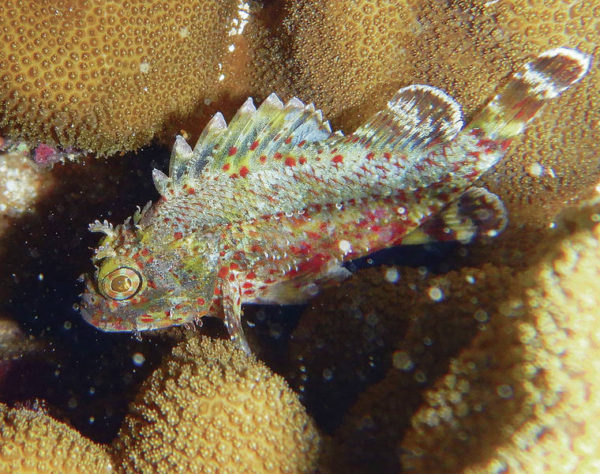

A spotfin scorpionfish hides in lobe coral.

A spotfin scorpionfish hides in lobe coral.

©2019 Susan Scott

The common English names that most of us call animals often come from the species name. For instance, Chaetodon tinkeri, named after the Waikiki Aquarium’s first director, Spenser Tinker, is called Tinker’s butterflyfish.

In choosing a scientific name, taxonomists sometimes use a term that describes the organism in some way, such as rubra (red) or hawaiiensis (endemic to Hawaii). Namers also regularly choose the name of the first person who first described the organism.

But not always. There’s a spider named Aptostichus barackobamai, a crustacean called Synalpheus pinkfloydi and a wasp termed Conobregma bradpitti. My favorite is a chewing louse named Strigiphilus garylarsoni after “The Far Side” cartoonist.

Just about any name goes as long as it’s not offensive and not your own — unless you pay for it. Some organizations let you name one of their newly discovered species after yourself or anyone you choose. At Scripps Institution of Oceanography, prices for the privilege are a tax-deductible donation ranging from $5,000 to $25,000.

Such marketing of scientific names is controversial, but it’s one way of raising awareness of the vast number of organisms on Earth still unknown. Of the estimated 8.7 million species that exist, only 1.2 million have been described and named.

Historically, naming organisms has been a slow and tedious process, but technology is speeding things up. Researchers can now determine the DNA code of organisms, catalog newly named species in databases and communicate the information instantly on the internet.

As to the Austrian-born Steindachner (1834-1919), my apologies. The man was, by all accounts, a professional master of zoology who would never have named a species after himself. In a 1921 issue of Science, David Starr Jordan, an ichthyologist and first president of Stanford University, states that Steindachner was “to his colleagues one of the most trustworthy and most devoted lovers of knowledge for its own sake.”

Scientific labels are hard to pronounce and remember, and as taxonomists learn more about evolutionary relationships, some names change. But we shouldn’t gripe. Before we can understand, protect and share information about the millions of organisms that share our planet, we have to know what to call them.