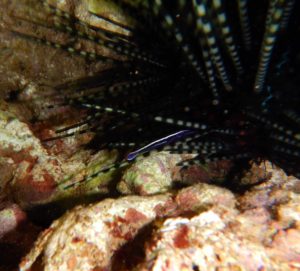

Two baby damselfish are sheltering among the spines of this banded urchin. ©Susan Scott

May 16, 2021

![]() The first time I saw the sharp-spined sea urchins the Hawaiians named wana, I thought they were plants, like some kind of underwater cactuses. But when I learned that wana (pronounced vah-nah) are animals that walk around on suction cup tube feet, eating anything they come across with a mouth called Aristotle’s lantern, well, my love affair with the creatures began.

The first time I saw the sharp-spined sea urchins the Hawaiians named wana, I thought they were plants, like some kind of underwater cactuses. But when I learned that wana (pronounced vah-nah) are animals that walk around on suction cup tube feet, eating anything they come across with a mouth called Aristotle’s lantern, well, my love affair with the creatures began.

And it goes on. Even after decades of snorkeling and diving among wana, I still find these odd animals fascinating, including several I noticed last week.

Not everyone is fond of long-spined sea urchins, because connecting with their needle-sharp spines is painful. Wana punctures on Craig’s foot were he first marine injuries I saw in Hawaii after he fell off his board windsurfing in shallow water. But if you don’t step on, or touch, a wana, a close look is well worth the time.

Craig’s foot after a fall on a Waikiki reef looked much like this unknown person’s. Craig left the brittle, backward-barbed spines in place, where they eventually dissolved on their own. This is accepted medical treatment unless the spine is in a joint or gets infected. Then see a doctor. Soaking in urine, vinegar, or meat tenderizer are myths that don’t help pain or healing. (In the BOOK tab, see our marine injury book, All Stings Considered, UH Press.)

Hawaii hosts several species of sharp-spine sea urchins that we Hawaii residents call wana, all bearing barbed spines that the animals wave toward you if you get too close. Sea urchins, however, cannot release, or shoot, their spines, which are attached to the skeleton by skin and muscles.

The most common wana we see snorkeling and in shallow water is called the banded urchin (Echinothrix calamaris), its long spines ranging from black-and-white, to gray, to all black. In young banded urchins, the shorter, slimmer inner spines are green or gold.

The mouth that Aristotle called a lantern is a 5-part set of teeth and jaws located on the underside of the sea urchin. On the top side of all wana is the animal’s anus enclosed by a balloon-like structure with a center opening that ejects wastes away from the creature’s body.

At center is the intact anal sac of a young banded sea urchin. Slim inner spines (a needlelike bunch clear on the right) are greenish. ©Susan Scott

We see this spotted balloon only in young wana, however, because a parasitic crab (Echinoecus pentagonus) gets inside nearly all individuals’ anal sacs, and eats them away. The female crab spends it life just inside the urchin’s rectum eating its white fecal pellets. The smaller males live outside among the spines. Once the anal sac is gone, sharp-eyed snorkelers and divers can sometimes spot the female crab.

The pink and white figure at center is this sea urchin’s parasitic crab after it ate the urchin’s anal sac. The crab was hard to photograph because it lay far inside the needlelike spines that the animal was waving at me. The white triangle on the left side of the crab is the front of its top shell, a distinctive feature for this species. For a good closeup see bit.ly/3tP6zY5 ©Susan Scott

Other marine animals seek the protection wana spines can offer, making the sea urchin a living fortress for shrimp and small fish.

![]() Triggerfish are among the few predators of long-spined sea urchins, but the urchin needs to be out in the open for the fish to be able to turn it over, and eat from the bottom. Because the nocturnal long-spined sea urchins rest during the day in nooks and crannies, they’re often hard to for us humans to observe, and for triggerfish to bowl over.

Triggerfish are among the few predators of long-spined sea urchins, but the urchin needs to be out in the open for the fish to be able to turn it over, and eat from the bottom. Because the nocturnal long-spined sea urchins rest during the day in nooks and crannies, they’re often hard to for us humans to observe, and for triggerfish to bowl over.

While snorkeling recently, I saw a flash of purple on a wana spine and was able to get a picture of a white-stripe urchin shrimp (Stegopontonia commensalis), below, hanging on in strong current.

This purple shrimp spends its entire life on a wana spine, eating whatever the sea urchin stirs up during its nighttime foraging. My camera also captured pink muscles that connect the spines to the body, thus enabling the spines to move. ©Susan Scott

![]() Since wana are nighttime feeders that tuck into reef cracks during the day, it’s hard to see who’s all sharing their lairs. As is often the case, my camera saw better than my eyes, and rewarded me during the download.

Since wana are nighttime feeders that tuck into reef cracks during the day, it’s hard to see who’s all sharing their lairs. As is often the case, my camera saw better than my eyes, and rewarded me during the download. ![]()

I took this picture of several cardinalfish hiding near this sea urchin’s spines. Unseen by me at the time, but caught on camera, is a brittle star (black arms on the right) and several marbled shrimp (above and behind.) It’s as good as hiding behind a snoozing dragon. ©Susan Scott

An exposed brittle star on an earlier day.

A marbled shrimp on a different day.

You can see why I usually stop near wana to see who has checked into the Bed of Nails Hotel. And even if I can’t see the guests, I always get a wave as I pass by.

Just a tiny flash of purple on this wana caused me to circle back for a closer look, turning this snorkeling excursion into a memorable day. ©Susan Scott