Craig snorkeling in 3-feet of water. Taha’a, French Polynesia. ©Susan Scott

January 29, 2021

“I’m terrified. You should be. Everybody should realize snorkeling is not a low-risk recreational activity to be taken lightly,” This quote by Kailua physician, Phil Foti, was in a recent Honolulu Star-Advertiser article titled “Snorkeling safety” (January 17, 2021.) The piece summarized a report issued by a multi-agency group called Snorkel Safety Study, www.snorkelsafetystudy.com/.

The report, and the newspaper quote, got a lot of attention at my house, as well as from my readers, several of whom asked my opinion on the dangers of snorkeling.

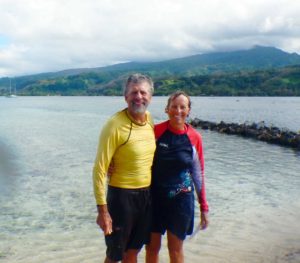

Craig and I often snorkel off our sailboat, Honu, (upper left.) Tahiti.

The Snorkel Safety Study speculates that a condition Foti coined Rapid Onset Pulmonary Edema, or ROPE, explains mysterious snorkeling deaths in Hawaii. (Pulmonary edema is when excess fluid collects, for a variety of reasons, in the lungs, filling the air sacs.) The report also hypothesizes that ROPE may be related to recent air travel, snorkel design, and heart disease.

The mention of ROPE sent Craig and me to the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed, a free search engine with access to 30 million biomedical articles from life science journals worldwide. We did not find ROPE. We did, however, find a recognized condition called SIPE, Swimming Induced Pulmonary Edema, an ailment that occurs in physically-fit swimmers.

The first SIPE report came from the Israel Naval Medical Institute in a 1995 issue of the British Medical Journal (BMJ 1995;311:361-2). Eight of 30 highly-trained military men experienced shortness of breath and pulmonary edema during strenuous swimming in calm, Mediterranean water of 73-degrees. A multitude of journal articles regarding SIPE incidents have followed, including several published in 2020.

So, yes, pulmonary edema while swimming is a thing, and that’s even without inhaling and exhaling through a plastic tube. Researchers have theories as to why this potentially-lethal lung disorder occurs while exercising in water, but no one knows how to avoid it. SIPE is relatively rare, but with millions of residents and visitors snorkeling in Hawaii each year, it’s likely a factor in some drownings.

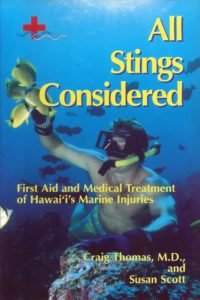

Craig and I coauthored a book called All Stings Considered, (bit.ly/3qQO2th) about the ways people can get in trouble in Hawaii waters, such as breaking waves, strong currents, jellyfish stings, free diving, coral cuts and more. Most marine injuries, hazards and treatments haven’t changed since we wrote the book in 1996, but a few have. In 2014, we added an insert with updated information about jellyfish stings, antibiotic use, and seasick medication. Our next addendum will include SIPE.

Those experienced with Hawaii’s waves and currents can make surfing, body surfing, and swimming look effortless, tempting novices to enter the water. Trouble, and sometimes tragedy, sometimes results. ©Susan Scott

Medical conditions, such as heart attacks, strokes, vertigo, and exhaustion in bodies unaccustomed to exercise, routinely occur in people on land. When they happen in the water, people can drown before help arrives, resulting in “unexplained” drownings.

Some difficulties, I never imagined. For example, there was my 20-year-old mainland friend, a fit lap swimmer, who jumped with me into deep water from a ledge, and began swimming freestyle, that is, turning her head to the side to breathe, while wearing mask and snorkel. The snorkel flooded, of course, and in her panic, she grabbed me, nearly drowning us both.

Since then, I never take novice snorkelers in deep water until we have a lesson, but that didn’t end the surprises. My small, slender, Midwest-visiting sister wasn’t in the water 10 minutes during our Hanauma Bay snorkel when she clutched me. “I can’t do this anymore,” she said, gasping for breath. She was so cold that her body had turned an unnerving bluish-white. Fortunately, I was able to get her, shaking, to shore.

Even with multiple warning signs, and helpful lifeguards, snorkelers get in trouble with hypothermia, fear, misunderstanding and other unpredictable circumstances. This kind Hanauma Bay lifeguard was helping a visitor with her mask. ©Susan Scott

During another Hanauma Bay swim, my 10-year-old nephew’s mask filled with water when he was in about 4 feet of water. He flailed and thrashed until I reached him and yanked off his mask.

“Why didn’t you just stand up?” I said, as he coughed and cried.

“Because we’re not supposed to stand on the coral!”

There’s also fear of fish. My Michigan friend began hyperventilating in her mask and snorkel, because she was so afraid of the marine animals that I was merrily pointing out. I had to work hard to calm her down enough to swim to shore.

We seasoned snorkelers may be thrilled to see a barracuda, but some visitors don’t know the fish are mostly harmless. Shark’s Cove. ©Susan Scott

Moray eels open and close their mouths to breathe. This causes panic in some snorkelers who mistake the motion for aggression. A Steindachner’s moray, Waialua. ©Susan Scott

These are just a few of my own experiences, but imagine how many other fearful events happen to the millions of people living in, and visiting, our island state intent on snorkeling in Hawaii’s warm, blue waters. Tragedies are bound to occur.

I’m glad that people are studying ways to minimize snorkeling-related drownings. I do not agree, however, that snorkeling is a high-risk activity that should terrify people. To lower the risk of drowning while snorkeling, rental shops, tour guides, and those of us who take our visitors snorkeling should emphasize that snorkelers be capable swimmers. If new to the sport, they should practice using the gear in calm, shallow water.

These Hanauma Bay visitors wisely practiced using their snorkel gear before heading into deeper water. ©Susan Scott

I highly recommend staying in shallow water. Nearly all of the amazing animals that I photograph and write about I find in water less than 5 or 6 feet deep.

One of the wonders of snorkeling is never knowing what you’ll see. Several years ago I discovered this seahorse in 1 foot of water on Oahu’s North Shore. I’m still thrilled by that find. ©Susan Scott

Importantly, make sure you can breathe normally through the snorkel you rent or buy. Craig and I have both used dozens of snorkels over the years, and have settled on a brand called Aqua Lung Impulse 3. It’s expensive, but worth it as an easy-breathing, water-excluding, snorkel. We have both borrowed full face masks to try out, but because they don’t allow for free diving, something we do often, neither of us liked them.

Craig free diving in Palau. Photo courtesy Ted Simon.

It’s wise for beginners to snorkel with a buddy who knows the learner’s fears and limitations.

Like most outdoor activities, of course snorkeling has risks, but that’s no reason to fear it or avoid it. My advice is to learn measures to minimize risks, and then go for it. During a Mexico trip in 1981, Craig helped me go snorkeling for the first time. You can see from this website how it changed my life. To me, the potential dangers in ocean swimming are well worth the joy I get in doing it.

Our niece, Kali, and her husband, Brad, Portland residents, started out as novice snorkelers. They listened to my tips, practiced their techniques, and are now comfortable snorkeling. ©Susan Scott