Published in the Ocean Watch column, Honolulu Star-Advertiser © Susan Scott

March 24, 2018

Because Hawaii is so far from the tropical Pacific, fish and coral larvae had to survive long periods adrift to get established here. As a result, the Hawaiian Islands host only about 620 fish species and about 70 or so kinds of corals. And so, after snorkeling in Palau, an archipelago teeming with 1,400 kinds of fish and 700-some corals, I wondered whether I’d be disappointed when I got back home.

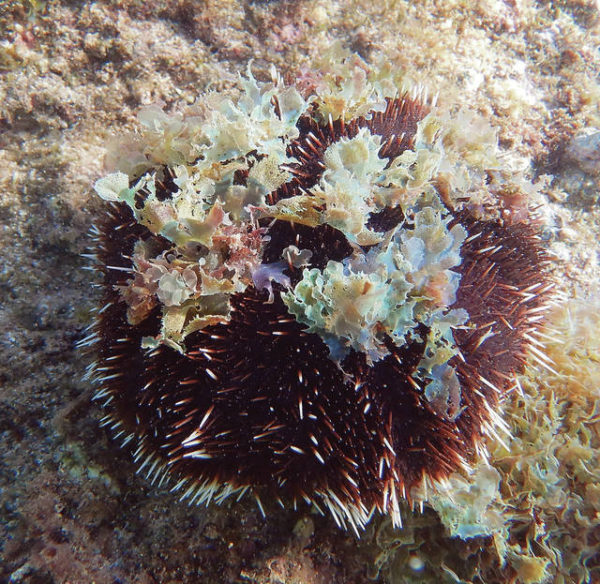

Susan Scott’s collector urchin in its opal sunbonnet.

Susan Scott’s collector urchin in its opal sunbonnet.

©2018 Susan Scott

Nope. Last week, to cool off in the sticky Kona weather, I took my mask and snorkel to a shallow reef for a swim and immediately saw two of my favorite marine organisms, one wearing the other for a hat.

My much-loved animal was neither fish nor coral, but a prickly ball of a thing called a collector urchin. On its top the well-named animal had placed several bouquets of my favorite seaweed, named Martensia fragilis.

This spectacular seaweed, growing in tufts about 2 inches tall, has no common name. But because its pink, green and blue pastel blades shimmer in the sun like opals, I call it opal seaweed.

The plant comes and goes in the place where I swim, but right now it’s blooming so brightly in the morning sun that the usually brown reef looks like a jewelry store.

Opal seaweed is native to the warm Indian, Pacific and western Atlantic oceans, growing from tide pools to waters 150 feet deep. It’s also native to Hawaii, meaning it got here without a lift from human hands or hulls, drifting hundreds or even thousands of miles to our islands.

Seaweeds reproduce in several ways. Some get around when pieces of blades break off and settle in another place. These are clones. Other marine plants take the genetic diversity route, producing eggs and sperm that they release in the water. This isn’t as random as it sounds because like animals, plants produce chemical pheromones that signal to their neighbors when it’s time to let loose.

Collector urchins keep seaweed growth in check — crucial for healthy coral reefs. After resting all day, at night the urchins roam the reef on tube feet gobbling up seaweed. When the seaweed is an invasive pest, as some species are in Hawaii, collector urchins may be the reef’s saviors, more than happy to eat the enemy.

Collector urchins, also called hawae maoli in Hawaii, also use their tube feet to cover themselves with whatever is handy, be it shells, seaweed, pebbles or plastic. Only the urchins know why they do this. It may be a disguise from predators, a sunshade or a way to store food. If seaweed is scarce in the vicinity that night, an urchin covered in opal or another seaweed can simply eat its hat.

I love visiting places with masses of fish and heaps of coral, but they’re by no means everything on a reef. Hawaii’s 500 seaweeds and thousands of invertebrates are enough to keep me happy at home.