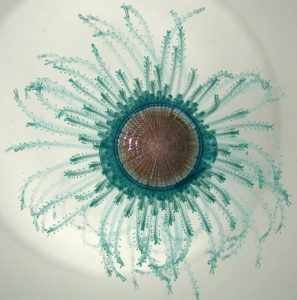

Blue button AKA Porpita porpita, Lanikai Beach. ©Susan Scott

March 9, 2021

“Don’t touch that!” a fellow beach walker said recently, as I bent to examine a blue button that had washed ashore. “I heard they sting.”

Really? I didn’t think these jellyfish relatives packed much of a punch since I’ve picked them up them on beaches numerous times and never felt a thing. Then again, calloused fingers probably aren’t a good test.

This tumbled blue button lost all but one of its tentacles. You can see portions of others on Craig’s finger. He felt no sting and had no rash. ©Susan Scott

Blue buttons are close relatives of hydroids, the stinging, fern-shaped organisms that often grow on rocks, boat hulls, and other items resting in shallow ocean waters. While snorkeling in Palau several years ago, I had an itchy rash on the inside of my wrist for a week after brushing against a white hydroid while taking a picture of a shrimp.

A hydroid colony, Palau. ©Susan Scott

Tahiti hydroids. ©Susan Scott

Being hydroid relatives, blue buttons have the potential to sting, but it’s rare. My literature search turned up a 2005 case report of a 37-year-old surfer who felt pain on his forearm while paddling on the coast of Japan’s Chiba Prefecture, which faces the Pacific Ocean. He noticed a raft of blue buttons, a species he had been in contact with in the past, but had no ill effects. This time, though, the surfer got an itchy rash that 4 days later developed blisters. They disappeared in 10 days without treatment.

This is the first and only occurrence of a blue button sting significant enough to warrant a write-up in a medical journal. So although some people may have a reaction to those tiny tentacles, blue buttons aren’t particularly hazardous to humans.

Tiny animal plankton, though, beware. Blue buttons sting and eat any living, drifting animal that the winds and currents carry them to, including crabs, fish, shrimp, worms, and the eggs and larvae of all.

This clear photo offers a good view of a blue button body with tentacles intact. Bruce Moravchik (NOAA), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

We only see these pretty little blue disks we call blue buttons when they get shipwrecked on Hawaii’s windward beaches during periods of strong trades. But even then, blue buttons are relatively rare here.

Lately, however, these warm water creatures are showing up in new places. One 2017 paper reports a blue button found off the coast of Turkey, the first since 1842. (Makes me wonder how that one got into the Levantine Sea, the eastern region of the eastern Mediterranean, back in the 19th century.)

Other single blue buttons have been reported for the first time in coastal Bangladesh and India. Whether the animals are expanding their range due to warming seas, if blue buttons are being transplanted to new places by seagoing vessels, or if these are rare flukes of the currents is unknown.

The blue button is well-named. Radiating from the flat, brownish, buttonlike body are bright blue tentacles that look feathery. But those are no fluffy feathers. The nobs contain stinging cells called nematocysts, common to all members of the jellyfish clan.

Blue buttons often lose their tentacles when picked up. We lifted this one with a clump of sand for a close view. ©Susan Scott

Like all jellyfish-type stings, whether you get a reaction from a blue button depends on what area of the body its tentacles touched, how many tentacles made contact for how long, and the individual’s susceptibility to stings.

These disklike animals contain an air bubble that allows them to float on the surface of all warm seas. Being so flat, however, leaves the wind with little to push against. Blue buttons, therefore, usually remain far offshore in their community of other wind-and-current drifters.

I carried these half-inch-wide blue buttons home in a container of sea water to view them in the comfort of my kitchen. The creatures lost most of their tentacles in the transport, and did not move. ©Susan Scott

Textbooks tell me that blue buttons amass by the thousands offshore. I’ve not seen this phenomenon during my offshore voyaging, but I live in hope. (Our 37-foot ketch awaits us in Australia.) In the meantime, when I find the rare, beached blue button here in Hawaii, I stop to admire its beauty, and consider the circumstances that separated this one individual from its offshore community. When your boat is the size of a button, that’s quite a passage.

Most blue buttons are about an inch wide, but they can grow larger. This one, pictured on a cuttlefish bone, was found on September 13, 2013 in Darwin, NT. Reported at jellyfishwatch.org